OVERDIAGNOSIS TODAY: BENEATH THE SURFACE

How Medical Labels Without Certainty Could Be Making us Sicker

By: Hannah Usadi

Diagnoses of psychological conditions have increased over the last two decades.

We are getting sicker.

But the it's more than that. So have other chronic medical conditions.

Some of this increase may reflect real shifts: rising obesity and metabolic illness, higher chronic stress, reduced social connection, and mental health impacts linked to heavy digital and social media use.

But not all increases reflect more illness.

Research suggests a portion of these rising numbers comes from something quieter and rarely questioned: overdiagnosis.

Why are we getting sicker?

I just wish I knew what was wrong with me.

Time: 2:38 am

For many people, a diagnosis is meaningful.

ADHD is a legitimate condition and a diagnosis can explain struggle, offer support, and open access to care.

But at the same time, the number of diagnoses has expanded well beyond original estimates.

To understand why, we need to step back and examine the broader trend.

This explains so much.

I have a pathological condition.

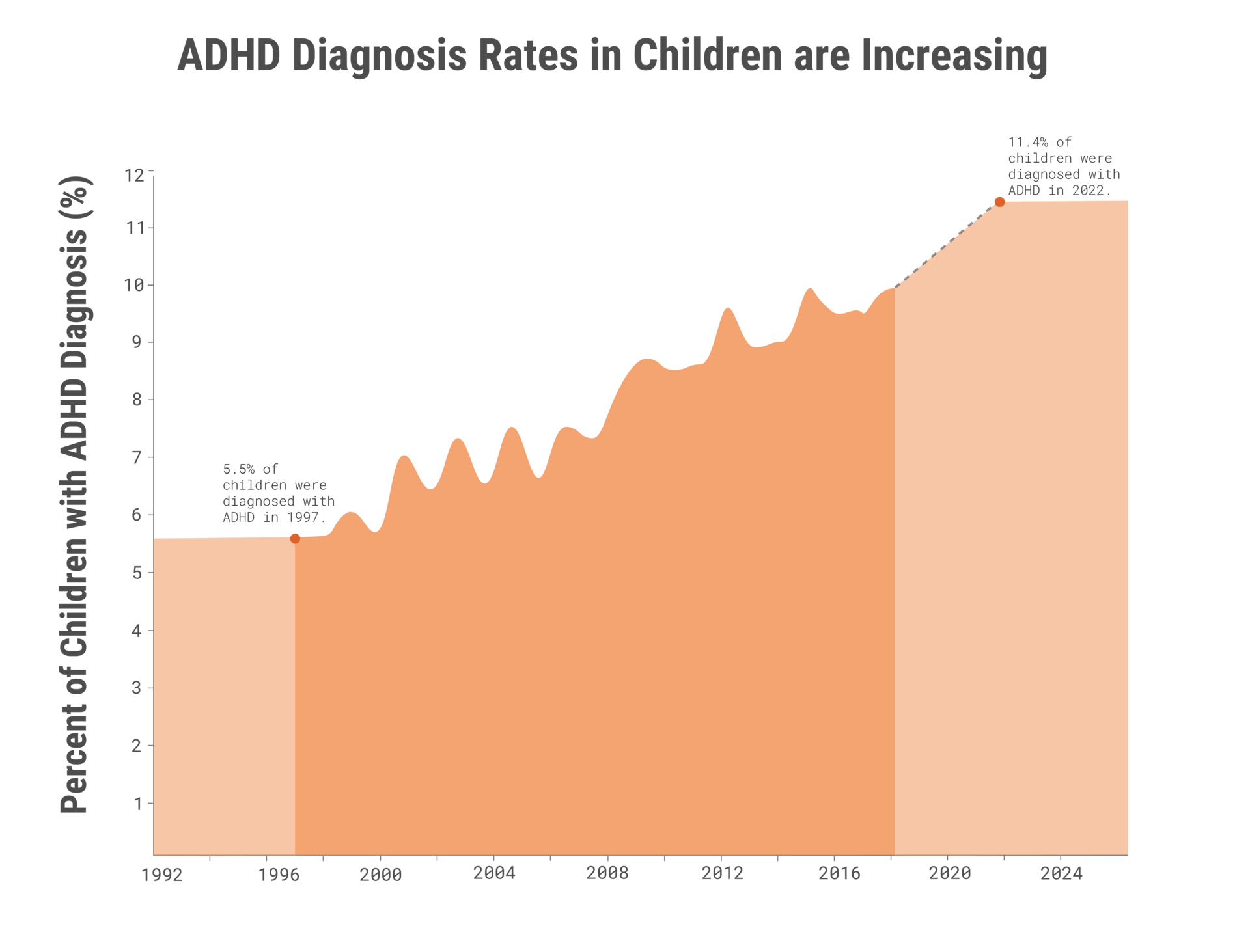

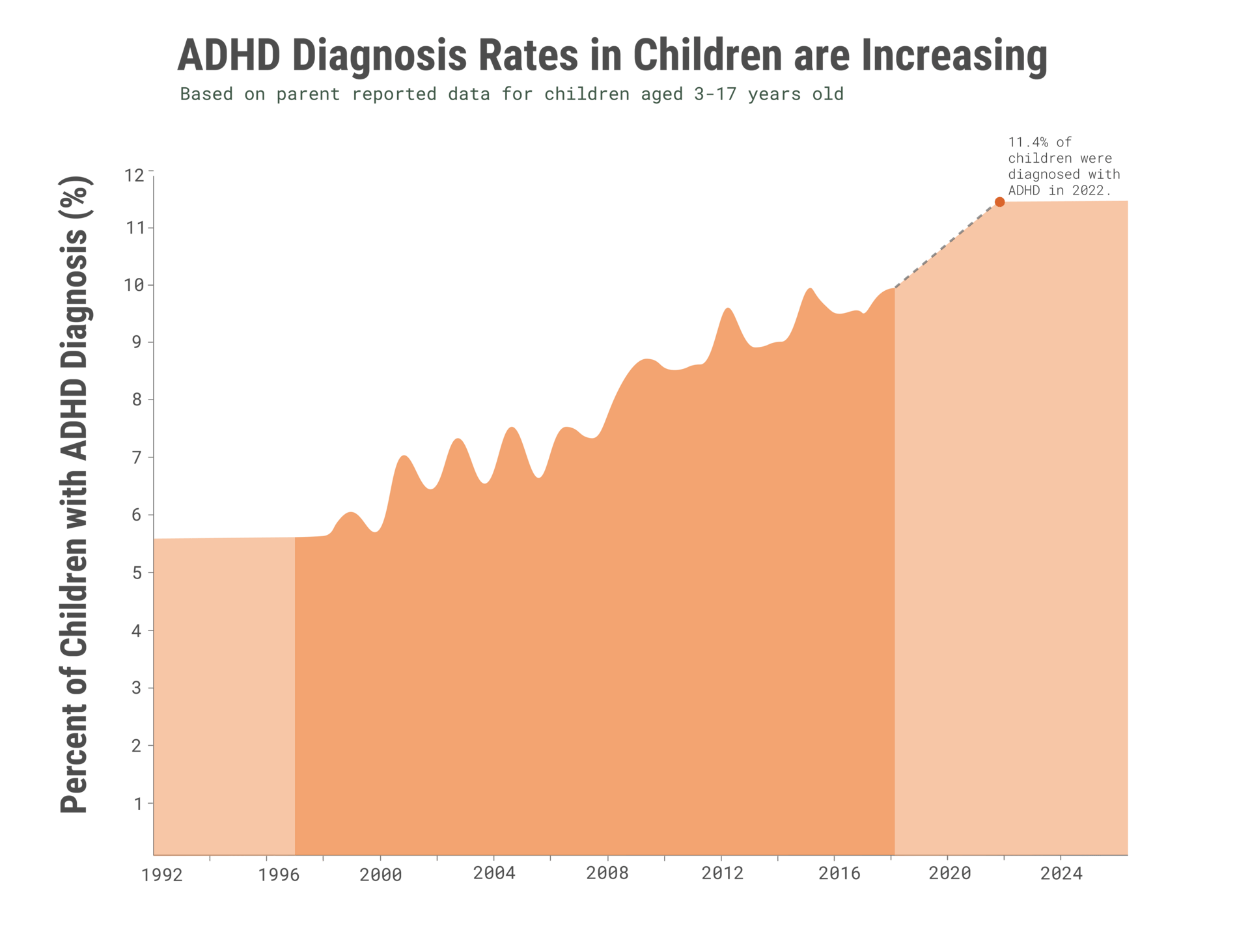

ADHD diagnoses among U.S. children have risen substantially over the last few decades. In 1997, about 5.5% of children aged 4–17 had been diagnosed with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder.

By 2022, this number climbed 11.4%, equivalent to roughly 7.1 million children.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov/adhd/data/adhd-throughout-the-years.html)

OVERDIAGNOSIS IN ADHD

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov/adhd/data/adhd-throughout-the-years.html)

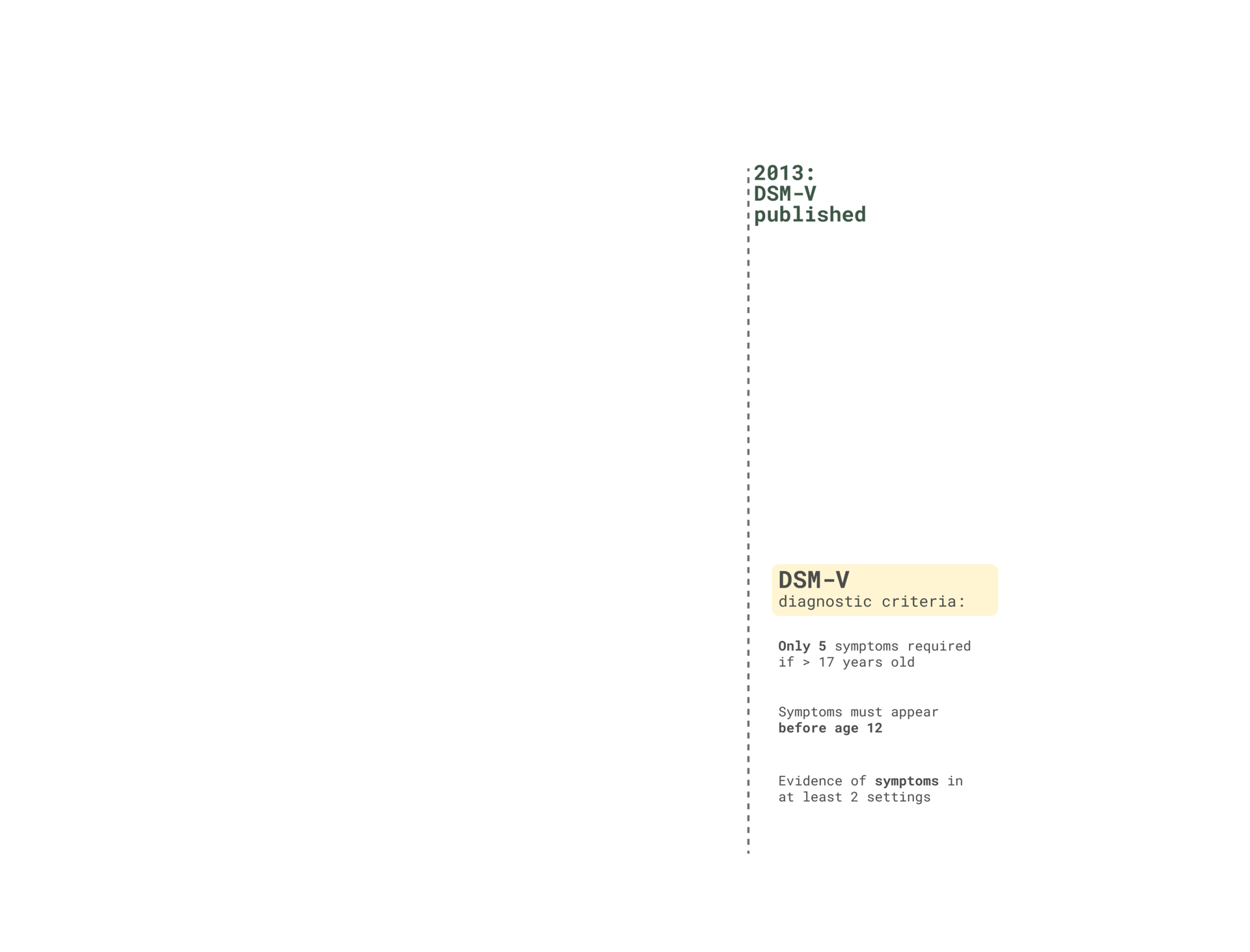

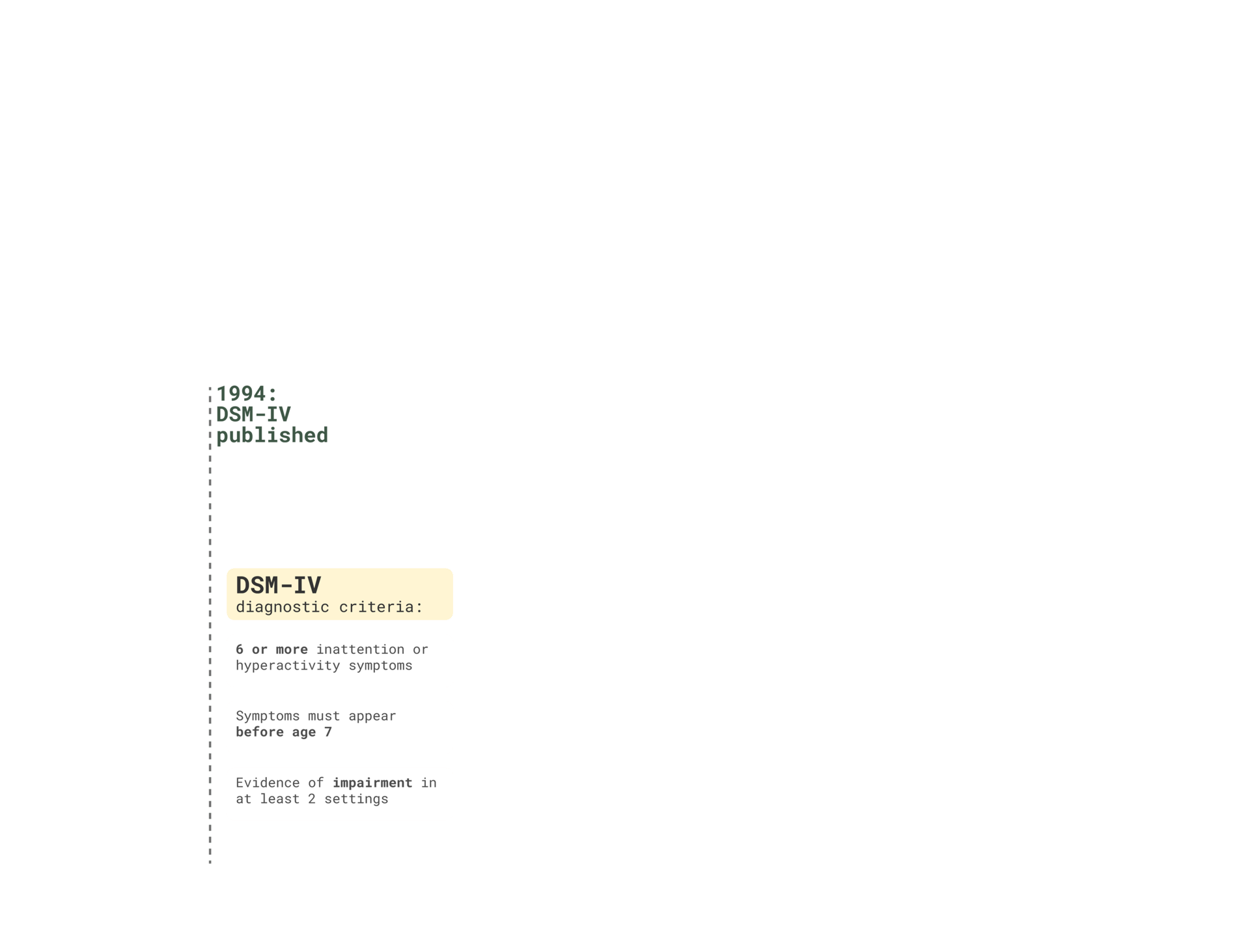

Some of this rise reflects better recognition and access to care. But a noticeable jump aligns with the transition from DSM-IV to DSM-5, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the system clinicians use to determine who qualifies for a psychiatric diagnosis.

The DSM is updated roughly every 15 to 20 years, and the move from DSM-IV to DSM-5 significantly broadened ADHD criteria: fewer symptoms were required, the age of onset increased from 7 to 12, and symptoms no longer needed to appear consistently across multiple settings.

As the rules expanded, so did the number of children who met them.

This map shows that diagnosis isn’t evenly distributed.

Some states diagnose ADHD at nearly double the rate of others: such as Louisiana, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Maine. And over time, the numbers continue to climb.

This variation suggests that where a child lives may shape whether their behavior is seen as personality, difficulty, or disorder: a pattern made possible by broad diagnostic criteria that leave room for interpretation.

Just as diagnosis varies by geography, it also varies by age. Younger children in the same classroom are diagnosed with ADHD at much higher rates than their older peers. The gap doesn’t come from a pathological disorder but from developmental stage. Younger children are naturally more active, more distractible, and less able to regulate attention.

When diagnostic criteria are broad, those ordinary age differences can be interpreted as symptoms of disorder.

Patterns in ADHD diagnoses suggest that growth over time reflects more than increased prevalence. Broader criteria, interpretation, and cultural narratives all play a role, allowing uncertainty to be translated into a diagnosis even when experiences exist on a spectrum.

Overdiagnosis in Lyme disease shows a different path to a similar theme, but where real symptoms persist alongside diagnostic uncertainty.

OVERDIAGNOSIS IN LYME DISEASE

"The scariest part was that I had no idea what was causing any of it."

"I wasn't sleeping."

"Then came the brain joint pain, the brain fog, then memory loss.

"The exhaustion started a few years back."

Jamie

"The exhaustion started a few years back."

"So I started going to private doctors. Ones who would actually run additional tests and take my problems seriously. "

"Every time I went to my doctor, I felt so unheard."

"One of them suggested it was Chronic Lyme Disease."

"I was so relieved to finally have a diagnosis and started antibiotic treatment right away."

"The first antibiotic treatment didn't work."

"But I'm on a stronger one and I'm hoping that will.

Reported Lyme disease were around 89,000 in 2023, yet estimates suggest half a million people are diagnosed and treated each year. This difference demonstrates how expanded testing and awareness can drive diagnosis rates up, more than just changes in exposure.

Researchers have studied Lyme disease for decades, especially the growing number of patients who believe they have active infection but show no biological evidence of one.

In a clinical study conducted at Yale, people diagnosed with Lyme disease were tested for Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria transferred by a tick that causes the disease.

The study found 60% patients diagnosed with Lyme disease did not have an active infection. Some had evidence of past exposure. Many had none at all.

82% of patients with no evidence of active Lyme disease reported persistent symptoms, compared to 25% of those with active lyme disease.

While patients were experiencing real symptoms, they were not a result of lyme disease.

When the patients were communicated their test results, less than half of those without Lyme disease agreed with the YLDC diagnosis and believed their results.

There has to be a medical explanation for my symptoms.

As unexplained symptoms persisted, some people began using the term Chronic Lyme Disease. But unlike acute Lyme, Chronic Lyme isn’t supported by scientific evidence and isn’t recognized as a legitimate medical diagnosis major scientific and public health organizations.

For some, the term felt validating. For others, it led to unnecessary, costly, and sometimes harmful treatments.

Over the years, many studies have been conducted to test whether extended antibiotic treatment could help people with persistent symptoms after Lyme disease.

None have shown meaningful or lasting improvement.

While the symptoms for these patients were real, they did not show evidence for infection of the Borrelia burgdorferi.

Yet, most non infected patients continued to seek out treatment and further testing.

Unnecessary treatment can carry real consequences.

In YCLD study, 61% of people who did not have evidence of Lyme disease still experienced adverse drug effects, ranging from mild reactions to serious complications. These were individuals without infection, yet they assumed the risks of treatment with no possibility of benefit.

While the antibioitics Jamie is on will not help him, he isn’t wrong to want someone to listen. We’re increasingly drawn to labels that promise clarity, and it’s becoming more common to treat everyday struggles as signs of an underlying condition.

The stories of ADHD, Lyme, and other rising diagnoses show how quickly uncertainty can turn into something medical, even when the label can addstress, confusion, or outright harm.

It has grown out of broader diagnostic criteria, new testing tools, the internet’s symptom culture, and a desire to find meaning or identity in illness. These forces are amplified by how medical information circulates online. In a recent review of nearly 1,000 social media posts about medical tests, most emphasized benefits, while very few mentioned possible harms, and only a small fraction acknowledged overdiagnosis (Nickel et al., JAMA Network Open, 2025).

O’Sullivan describes “illness identity” as the roles and attitudes people take on once they are diagnosed. When a diagnosis is treated as an answer rather than a starting point, that identity can take hold. Research suggests that identifying too strongly with a diagnosis can sometimes worsen health outcomes, especially when the evidence behind the label is uncertain.

Instead of rushing to conclusions, this leaves an open question:

This shift toward overdiagnosis is a modern one.

How do we take people’s suffering seriously without overlooking the limits and consequences of diagnosis?

Shared uncertainty offers a different approach: acknowledging what we don’t know while still providing care and support.

A lot of diagnoses don’t emerge because certainty exists, but because uncertainty feels unbearable.

“Wouldn’t a better strategy be a public health campaign aimed at the entire population, rather than the expensive and anxiety-provoking medicalisation of 50%?" (O'Sullivan).

Treatments like insulin and vaccines save lives, but a lot of progress in public health has historically come from like clean water, better food, and safer living conditions.

Many of those people receiving a pre-diabetes diagnosis will end up monitored, worried, and carrying the weight of an illness.

O’Sullivan uses prediabetes as a good example. In the United States, about 96 million adults qualify for that label - nearly half the country!

If the goal is a healthier population, diagnosis alone may not be the answer.

Instead of emphasizing the labeling of illnesses that manifest, we could better support public health by shifting our investments to increased access resources that prevent the root cause of diabetes, such as a healthier food system, walkable neighborhoods, and support for long-term habits.

The alternative to overdiagnosis isn’t dismissing people’s experiences.

It’s supporting people without always turning uncertainty into a diagnosis through monitoring, public health, and symptom-focused care.